By Bailey Chenevert

Buy small and buy local is popular messaging amongst impact-conscious consumers. It’s generally the right idea, but how can we be sure that products are exactly what they appear to be? Grocery store shelves are overflowing with options, but scrutinizing and casual consumers alike can be fooled by the supposed smorgasbord. The truth is, a lot of stores don’t offer much of a choice for where your money goes at all.

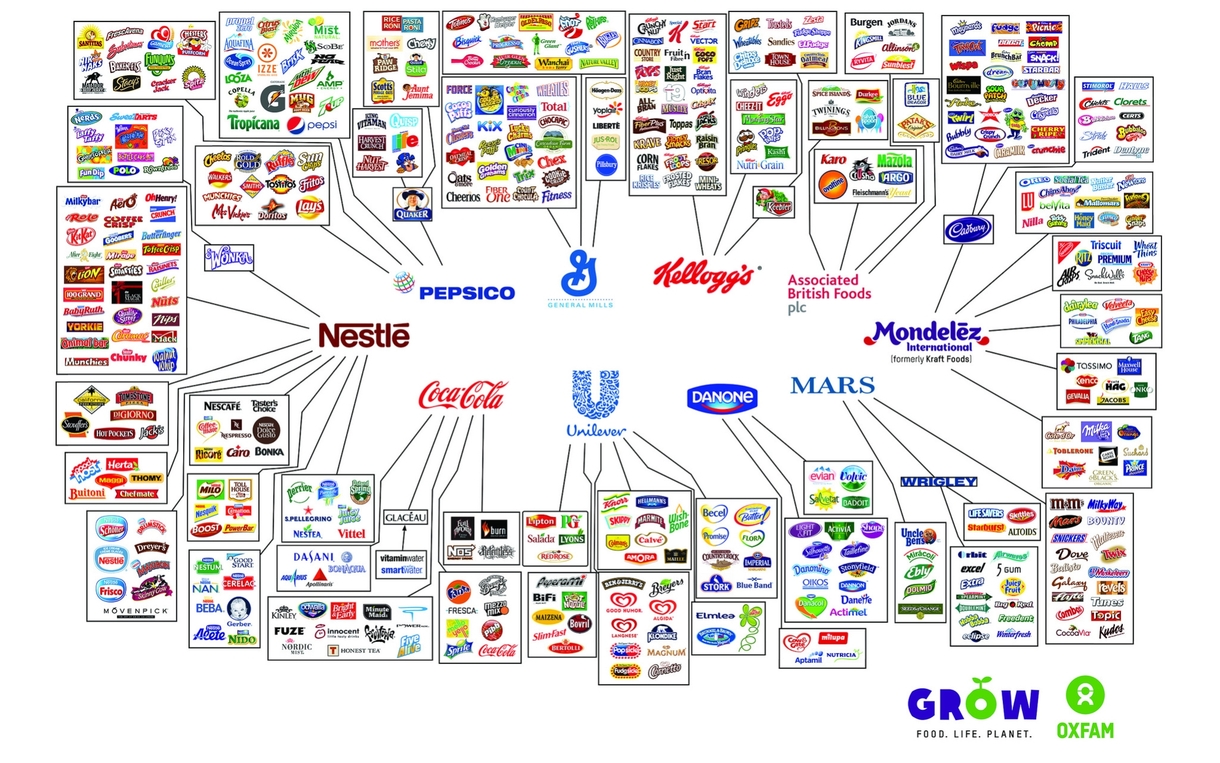

In 2014, Oxfam International, a charity organization, highlighted how hundreds of food brands are owned by the same ten companies in this graphic. It went viral as everyday consumers found out how megalith corporations create an “illusion of choice.”

Did you know that Oreo is owned by Mondelēz International, a massive snack company that has made over $25 billion in revenue? Maybe this isn’t so surprising – Oreos are sold just about everywhere and hardly have a small-town bakery reputation – but did you also know that Mondelez owns 52 other snack brands, including the popular Tate’s Bake Shop Cookie brand? Their packaging is a stark contrast to Oreos. Shoppers that want to spend their sweets budget on something a little less corporate may be sold by Tate’s quaint independent Bake Shop look, not knowing that some of their money is going into the same corporate-giant pockets as Oreo. Tate’s own website footer doesn’t even mention that it’s owned by Mondelēz. In order to find this information out, you’d have to look at a press release on Mondelēz’ site from 2018. While the statement makes clear that there’s a level of independence maintained as a result of the acquisition between Tate’s and Mondelez, it doesn’t change the fact that any purchase of Tate’s cookies ultimately contributes to Mondelez’ corporate bottom line (and consequently all of their corporate impacts and practices).

To be clear, we’re not writing this blog to dissuade you from supporting your favorite cookie brand, but rather to help lift the veil of the illusion of brand ownership diversity that permeates just about every consumer category, not just cookies. A 2017 article by Insider gathered charts like Oxfam’s portraying the illusion of choice that exists in beauty supply stores, clothing stores and even liquor stores. This 2019 article by The Guardian got even more specific, going through a typical day’s worth of products. One example showed that 85% of cereal sales were made by just four companies.

The Pareto Principle is a general rule popularized by economist Vilfredo Pareto that designates 80% of consequences to just 20% of causes. Also known as the 80/20 rule, this principle applies to many situations, be it 80% of restaurant reviews coming from the same 20% of customers, or, in this case, 80% of the products we buy being sold by the same 20% of producers. It’s almost impossible to report an exact figure because everyone’s consumption habits look different, but if you take household inventory, you’ll probably find that a lot of your stuff is owned by just a few companies.

There’s no denying that a relatively small group of companies control much of the world’s economy. In fact, in 2018, 69 of the world’s 100 wealthiest economic entities were corporations, not governments. But how did we get here, so vulnerable as consumers to this illusion of choice?

The narrative of modern consumerism is ripe with anecdotes of manipulation and mass marketing. In the 1920s, the U.S. saw the beginnings of mass marketing so familiar to the world today. Business leaders and economists needed a way to amp up consumerism to match the exponentially growing powers of production. Thus, businesses advertised their products constantly and sold the idea that consumption was the “escalator of desires” or “stairway” to heaven for the average consumer. Consumption propaganda intensified after WWII when bolstering the economy became a priority of government and business leaders alike.

Before we got to the point of seeing 6,000-10,000 ads a day, mass marketing tactics and consumer propaganda became standard practice to change the way we think about consumption and life satisfaction. Psychological obsolescence is the feeling we get that products we have are obsolete, whether or not they are. The intention is to encourage the average consumer to keep replacing their stuff indefinitely. One way psychological obsolescence is achieved is by marketing new trends all the time, making styles and products seem outdated. Similarly, planned obsolescence is the intentional design of inferior products that become useless, prompting replacements as well.

Why do corporations create and maintain such illusions as psychological obsolescence and diversity of ownership?

Remember earlier when we mentioned Mondelēz International’s $25 billion of accumulated annual revenue? Despite the impressive figure, they still fall behind several other companies, including Coca-Cola, who’s accumulated more than $37 billion in annual revenue and has significantly more brands (500+) than Mondelēz’ 52. Major companies continue to profit from changing consumer trends utilizing the different brands under their umbrellas.

For example, more socially-conscious consumers (a rapidly growing demographic) may buy All Good diapers instead of Pampers. They may be sold on its friendly and charitable packaging, but don’t know that both brands are subsidiaries of Procter & Gamble, another of the world’s biggest producers of consumer goods.

Corporations know that consumer tastes are changing, and they’re currently gobbling up popular independent brands, a practice termed “corporate consolidation” and keeping the ownership relationship opaque as to not alienate the independent brand’s loyal customer base. There’s nothing to fault the small brands either from taking these acquisition deals, it often means positive economic outcome for all of their workers and the communities in which they operate. Plus, given that the largest consumer goods producers are also often the largest owners of distribution channels into retail, it’s almost impossible to not take an attractive acquisition deal as a small, independent brand.

Impact-conscious consumers may feel blindsided when realizing they are giving their money to the same 10 corporate giants, but becoming more aware of this illusion is the first step to dismantling it. When independent brands are acquired by a corporate parent, it’s almost always announced via a press release, but often, as is the case for brands that have an independent appeal like Tate’s, that’s the extent of where this information is shared. And the intentional masking of the parent ownership to the everyday consumer on packaging and websites post acquisition remains. Here’s a list of brands that you may be surprised to find are also owned by corporate giants:

- Mrs. Meyer’s (S.C. Johnson & Son)

- Method (S.C. Johnson & Son)

- Annie’s (General Mills)

- KIND (Mars, Inc.)

- Larabar (General Mills)

- Tom’s of Maine (Colgate-Palmolive)

- Kettle (Campbell Soup Company)

By no means are we encouraging consumers to never buy from these brands or big corporations in general; the way our current consumer environment is set up, that‘s nearly impossible for a lot of people. Additionally, credit should be given to the small brands who manage to maintain their small-shop missions after being bought out by large corporations (as was the case with Tate’s independent Bake Shop operations and production). Another example, when Ben & Jerry’s was acquired by Unilever, an independent board of directors was appointed to uphold the company’s integral social missions, like campaigning for same-sex marriage.

The best course of action that we, as consumers, can take in our efforts of trying to make a greater impact with our purchases can be twofold: First, if you’re committed to buying independently and not from large multinational corporations, make sure you do your research because there is often more than meets the eye. You can do this when you sign up for Cluey as all parent company ownerships are made transparent. Second, if you love a brand even if they are corporate-owned, learn about that corporate parent’s impacts on people, the planet, and politics, and make your voice heard on the changes you want to see them make. Again, with Cluey, you can share your reaction to a brand’s impact, and we anonymize and aggregate your reactions alongside other consumers to share that message back with the corporations.

By reading this blog, you’ve already taken the first and most important step – being informed. So, feel free to go into your next late-night cookie run armed with information.

——————————————————————————————-

Bailey Chenevert is a freelance journalist and guest editorial contributor for Cluey Consumer. As a recent 2020 college graduate from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, Bailey supplemented her studies as both a research assistant and a student editor at La Louisiane. Bailey is passionate about impartial reporting on consumerism and the impacts that fashion brands have on our modern world.